What Is a Gimbal? The Only Must-Have Accessory for Smartphone Videographers

Share

The pace of innovation in smartphone cameras defies belief. Want a point of reference? Take George Lucas’ “Star Wars Episode II – Attack of the Clones”, released in 2002.

You know, that low-budget art house flick that couldn’t afford proper camera equipment?

That film, one of the first major forays into all-digital cinematography, used cameras that topped out at 2K resolutions.

If you own an iPhone or Android phone that was released after 2015, then you enjoy the ability to shoot 4K video using a camera that fits in your pocket. That’s right. In a little over a decade, consumer tech more than doubled the resolution of top-tier, big-budget cinematic equipment.

It’s a very good time to be an amateur — or even just a frugal professional — videographer.

But something doesn’t quite add up. It’s usually easy to spot the difference between a smartphone video and something shot on a high-end camera rig. If we’re carrying around high-end video equipment in our pockets, why doesn’t everything we shoot look cinema-quality?

More often than not, the key difference isn’t in the resolution, but in the way the camera moves.

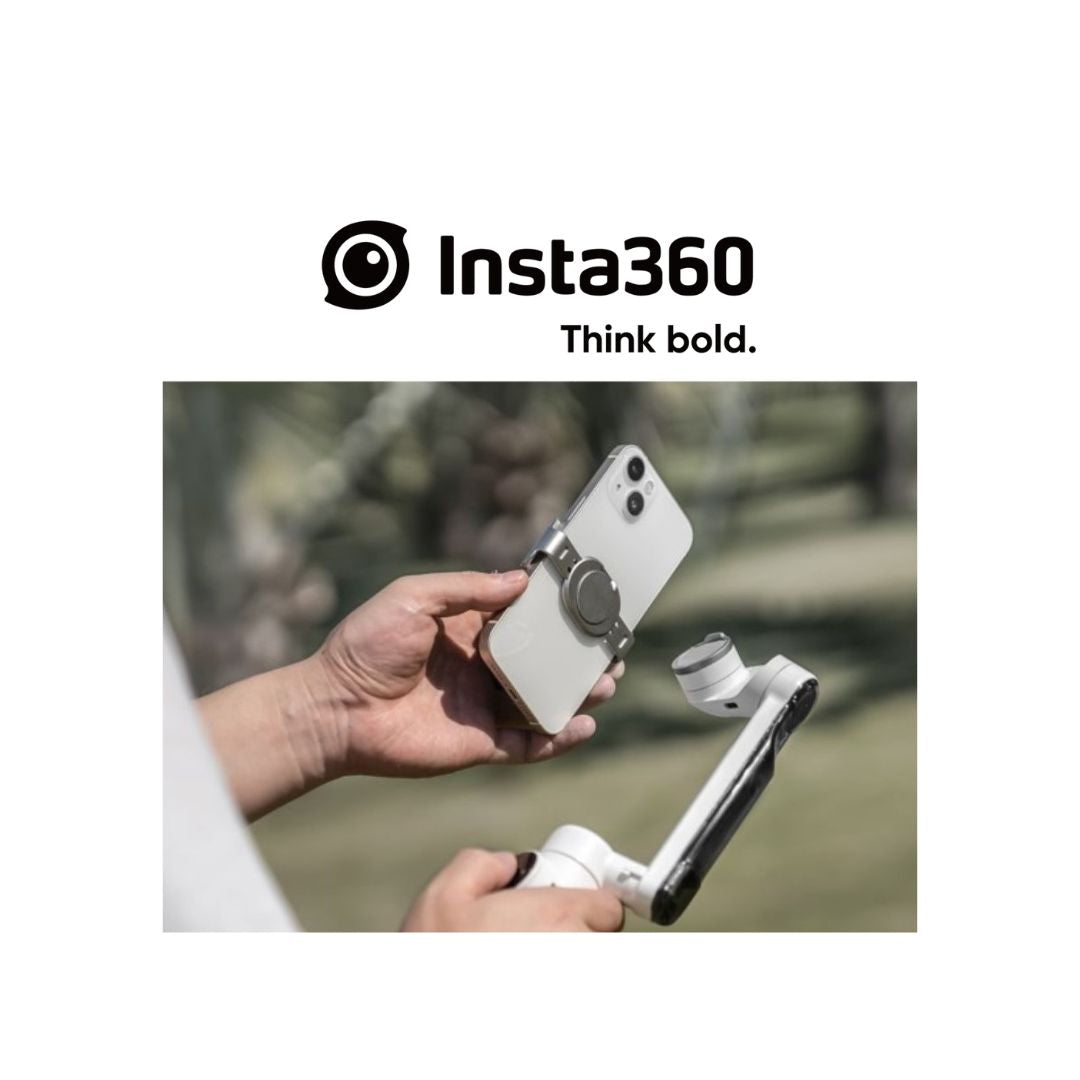

That’s where gimbals come in. Gimbals are powerful tools that connect to your smartphone to give you silky-smooth footage no matter how you move your camera.

It’s a little like a mech suit for your camera that makes it invincible to unwanted shakes and vibration and elevates your smartphone footage to cinematic quality.

A New Spin on an Old Idea

Since the time we started moving cameras, we’ve had to deal with the problem of unwanted camera movements. For most of film history, truly effective stabilizing equipment was reserved for top-dollar productions and expert technicians.

The iconic “steps” scene in Rocky was shot on a then cutting-edge Steadicam rig, which went for about $60,000 at the time.

But in the early 2010s, with the advent of smartphone photography and ever-more-powerful consumer DSLRs, manufacturers started to think smaller.

Soon, the handheld gimbal was born, first for DSLRs and soon after for smartphones.

Early entries in the genre were not nearly as powerful as today’s, but the basic concept hasn’t changed much: A camera is mounted on a mechanical, stabilizing arm that uses sensors and motors to correct for unwanted movements in real time.

In fact, the concept of gimbal goes back much further than the early 2010s. The basic idea — albeit for a gimbal that was used to stabilize ink pots and incense burners, not cameras — was drawn up by the Greeks in about 200 BC and by the Chinese soon after. And gimbals have been critical pieces of nautical technology, used to ensure that navigational equipment remained stable in the face of choppy seas, for thousands of years.

What kinds of movements can a gimbal correct?

If you’ve ever seen a simple gyroscope, you know the basic principles that are at play inside a gimbal.

Visualize your smartphone in your hand.

- If you twist your wrist side to side, that’s the pan axis.

- If you tilt your wrist forward and backward, that’s the tilt axis.

- And if you change the orientation from portrait to landscape, that’s roll.

Every object in three-dimensional space rotates on these three axes, and if you now imagine a classic gyroscope composed of three interlocking rings, you’ll see that the motion of each of these rings corresponds to one of these axes of motion.

True to its name, a gimbal is essentially a very high-tech gyroscope. And as your camera moves in any of these directions, its internal motors compensate with an equal but opposite motion.

Gimbals come in two basic flavors: 2-axis and 3-axis.

3-axis gimbals cover all three of the above-mentioned rotational axes, while 2-axis gimbals cover only tilt and roll. While some experienced videographers may be able to get good performance out of a 2-axis gimbal, 3-axis gimbals offer more versatility and are now the industry standard. In general, 2-axis gimbals are better suited to still photography and videography from a fixed vantage point, as opposed to dynamic shoots.

What’s an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU)?

Unwanted camera movements don’t happen only on the three rotational axes. Your camera might also shake by moving along the front-back, left-right or up-down axes.

Advanced gimbals, such as Insta360 Flow, use an instrument called an inertial measurement unit, or IMU, to measure every motion of your camera. This collection of sensors combines the rotational sensors of the gyroscope with additional measurements from the gimbal’s accelerometer, which measures acceleration in any direction. In effect, an IMU is an impressive-sounding word for the same kind of system your intestines use to give you that funny feeling when you take off a little too fast at the green light.

Why does a gimbal need to be outside the camera?

While gimbals can be very lightweight and portable (the best ones fold down very compactly), they are nevertheless one extra piece of gear for your kit.

You might wonder why they need to be outside of the camera at all. If we can correct for unwanted motion, why not just do it inside the camera?

The answer is that smartphone camera bodies are fundamentally too small to allow for the type of instrumentation needed to mechanically stabilize dynamic camera movements.

With built-in stabilization, you make one of two trade-offs: (i) Either you use optical image stabilization that attempts to apply a limited form of mechanical stabilization within the extremely restricted confines of a smartphone body and produces subpar results, or (ii) you use digital stabilization that simply crops down an image, attaining somewhat better stabilization at the expense of noticeably worse resolution and image quality.

This is why it’s necessary to use an external accessory that combines portability with precision.

What’s a brushless motor?

All motors have two core parts: the stator, or stationary part, and the rotor, or rotating part.

In a traditional brushed motor, there are physical points of contact, called brushes, that connect the rotor to the stator. The stator passes electrical current to the rotor via the brushes, where it is converted into mechanical energy.

Brushes generate heat, friction, and noise and they wear down over time, none of which are traits you’d appreciate for a piece of gear that’s next to your camera during a shoot.

Brushless motors, on the other hand, transfer energy from the stator to the motor using magnetic fields. This allows for silent operation and the extreme precision needed to make tiny adjustments on the fly, exactly what’s needed for a high-end gimbal.

How does the gimbal know which movements to correct?

If a gimbal can correct for motion in any direction, how does it avoid overcorrection? After all, many camera motions are intentional.

This question doesn’t have such a simple answer.

The decision of which motions are allowed and which aren’t come down to a series of sophisticated algorithms and heuristics that allow the gimbal’s sensors to distinguish between intentional maneuvers and unintentional jitters.

Advanced AI, like that used by Insta360 Flow, is helpful for nailing the difference.

Also, user-controlled shooting modes can tell a gimbal what type of motions to look out for in a given context. Insta360 Flow, for example, uses Deep Track 3.0, which allows you to lock onto any subject and let the gimbal do all the work of smoothly tracking and framing your subject.

What to consider when looking for a gimbal?

Weight, portability, and battery life are key considerations in choosing a gimbal. You’ll also want to evaluate the software support for your gimbal. Advanced controls are no good if the app used to calibrate them is overly complex, so your gimbal app can be a large factor in ensuring that you get the most out of it. Some, such as Insta360 Flow’s, also offer a range of post-processing features and effects